Medical Molding: When the Process Itself Becomes the Product

Medical molding is not just industrial manufacturing with a stricter label. It is a completely different discipline where the cost of failure isn’t a warranty return—it’s patient safety.

If a plastic housing on a consumer router cracks, it’s annoying. If a connector in a pacemaker fails due to internal stress, it’s a catastrophe.

Because defects like chemical contamination, internal stress, or weak weld lines are often invisible in the finished product, we cannot rely on inspection alone. We have to control the physics of the process itself.

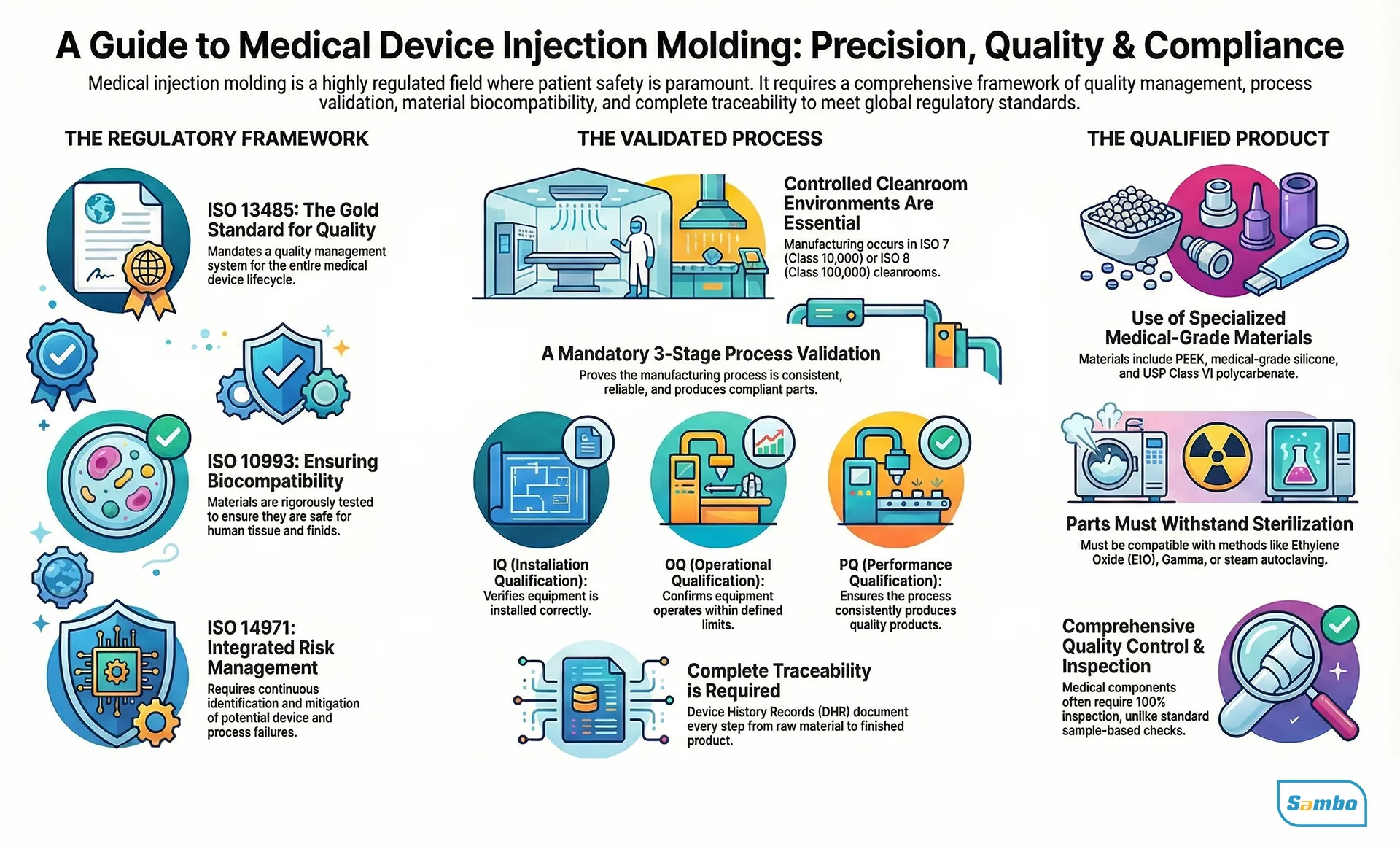

The Regulatory Reality – ISO 13485

You cannot operate in this sector without a proven system. The standard is ISO 13485 (specifically the 2016 version).

This standard categorizes medical molding as a “Special Process” (Section 7.5.2). This classification is critical. It means that because we can’t fully verify the output (you can’t see inside a solid plastic part to check for stress without destroying it), the process validation is the only proof of quality we have.

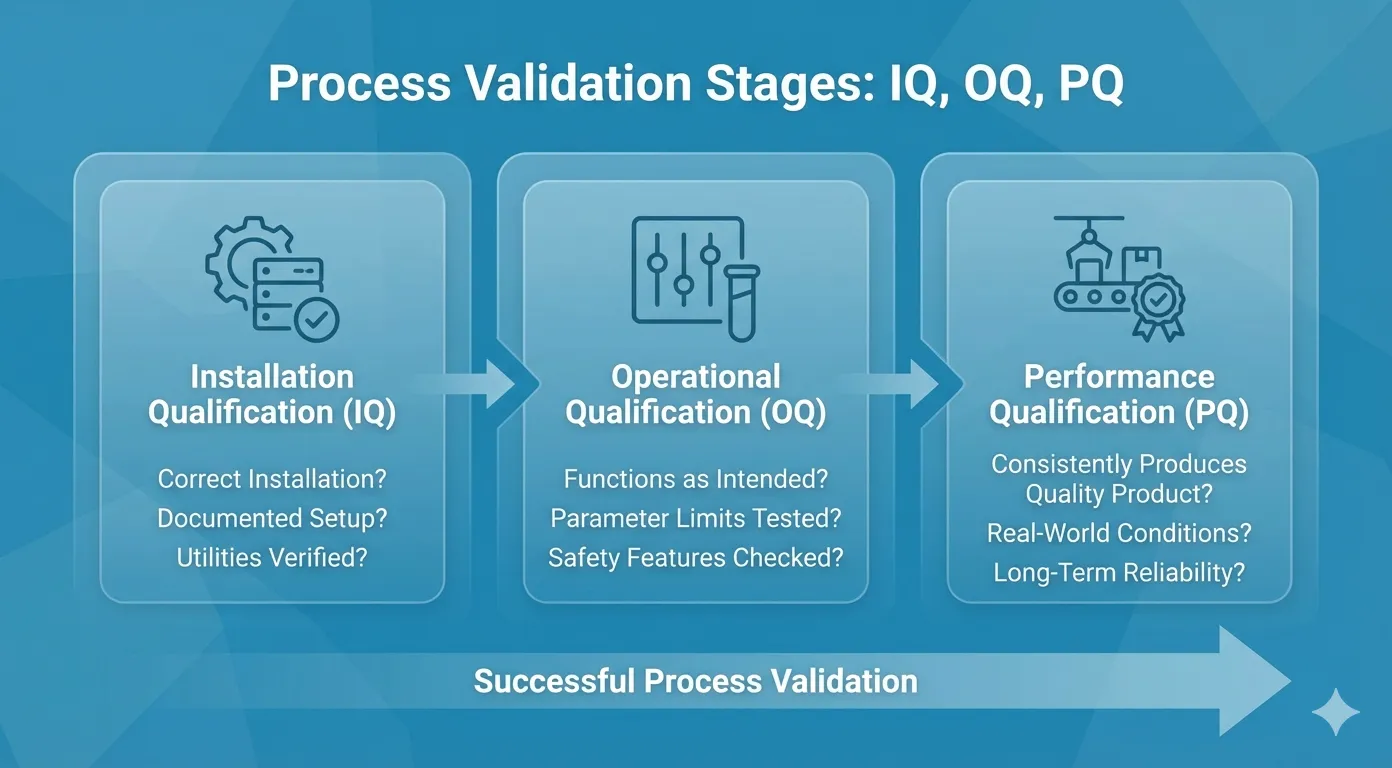

Process Validation: IQ, OQ, PQ

We don’t just “dial in” a machine. We stress-test it using a three-stage validation structure.

- Installation Qualification (IQ)

First, we check the hardware. Is the injection molding machine installed correctly? Are the chillers and dryers compliant with specs?.

- Failure Record: I’ve seen projects stall here because calibration records for a dryer were missing. If the auxiliary systems aren’t verified, nothing else matters.

- Operational Qualification (OQ)

This is the stress test. We define the operating limits by intentionally pushing the medical molding process.

- Method: We use Design of Experiments (DOE).

- Action: We fluctuate Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) like melt temperature and cycle time to their high and low extremes.

- Goal: We need to find the point where the process fails (e.g., short shots or flash) to establish a safe “validated operating window”.

- Performance Qualification (PQ)

This is the marathon. We run the machine under normal production conditions for extended periods.

- Metric: We look at Cpk (Process Capability Index) to prove that we can hit the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) every single time, not just when the engineer is watching.

Documentation: The Device History Record

If a part fails five years from now, we need to know why. The Device History Record (DHR) is our black box. It tracks:

- Raw material lot numbers.

- Production dates.

- Operator IDs.

- Specific process parameters used for that batch.

Material Selection for Custom Medical Plastic Parts

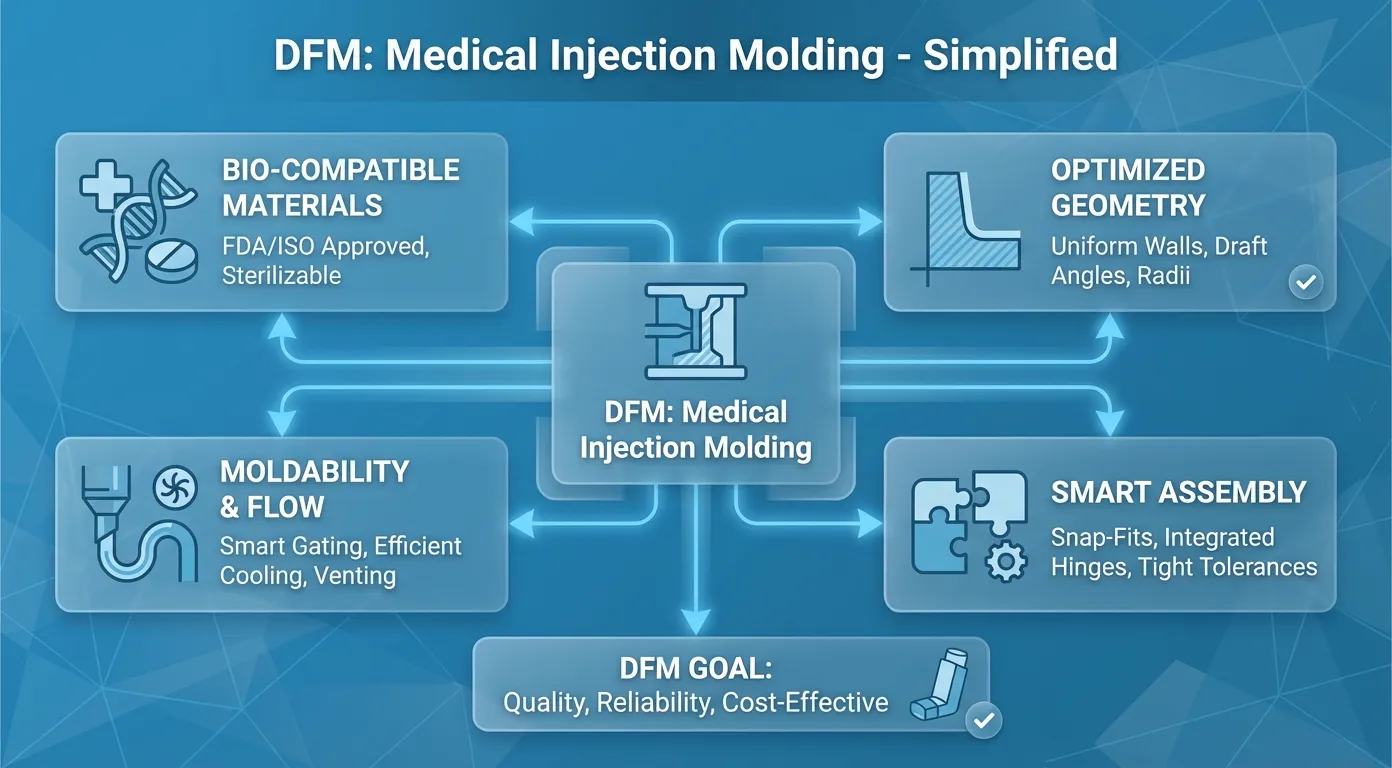

Choosing a resin for Custom medical plastic components is an engineering trade-off between mechanics, chemical resistance, and sterilization stability. But in high-precision medical molding, the non-negotiable factor is always biocompatibility (ISO 10993 or USP Class VI).

Here is how we select common thermoplastics:

- Polypropylene (PP):It has low viscosity, which means it flows easily into the mold. It’s cheap and chemically resistant.

- Use case: Syringes, test tubes, spacers in knee replacements.

- Polyethylene (PE):

- HDPE: Rigid and moisture-resistant. Perfect for medicine bottles.

- UHMW (Ultra-High Molecular Weight): This stuff is incredibly tough. It has exceptional wear resistance, which is why it’s used in orthopedic implants (like the bearing surface in a hip joint).

- Polycarbonate (PC):It’s transparent and tough.

- Use case: Oxygenators, diagnostic cartridges, protective masks.

- PEEK:This is high-end. It resists high temperatures, radiation, and harsh chemicals. It maintains dimensional stability even under stress, making it a go-to for structural implants.

Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR)

Sometimes plastic isn’t enough. If you need flexibility or stability in extreme temps (-60°C to 180°C), medical molding engineers turn to LSR.

The process (Liquid Injection Molding or LIM) is backward compared to plastic:

- Mix: We take Compound A (base) and Compound B (catalyst) and mix them 1:1.

- Inject: The material is cool and low viscosity (it flows like water compared to molten plastic).

- Cure: We push it into a hot mold (150°C to 200°C). The heat triggers the crosslinking reaction instantly.

- Failure Risk (Inhibited Cure): The platinum catalyst in LSR is sensitive. If it touches sulfur, amines, or nitrogen oxide, it gets “poisoned” and won’t cure.(Note: This is why we can’t have certain organic rubbers anywhere near the LSR machine).

The Physics of Molding: Critical Process Parameters

To ensure consistent quality in medical molding, we have to control the variables.

1. Melt Temperature

- The range: For PA 6.6, we run 280°C–310°C. For ABS, it’s 220°C–260°C.

- The risk: If it’s too low, the mold doesn’t fill (short shot). If it’s too high, the polymer degrades and loses strength.

- Mold Temperature

We use channels to heat or cool the mold. This controls how the plastic crystallizes.

- Trade-off: A hotter mold gives a better surface finish but takes longer to cool, costing money.

- Packing Pressure

After injection, we don’t just stop. We hold pressure (V-P switchover) to pack more material in while it cools.

- Calculation: Plastic shrinks volumetrically as it cools. If we don’t pack enough new material in to offset that shrinkage, the part surface collapses (sink marks).

- Cooling Time

This eats up 50-80% of the cycle time.

- Defect: If you cool it too fast or unevenly, one side shrinks more than the other, causing warpage.

Sterilization Compatibility

Your part is likely going to be sterilized. The material has to survive it.

- Steam Autoclave: High heat/moisture. PEEK or PP handles this well; others might melt or degrade.

- Ethylene Oxide (EtO): Good for heat-sensitive parts, but the gas is toxic. The material must be able to “breathe” it out during aeration.

- Gamma Radiation: Efficient, but aggressive. A 2.5 Mega-Rad dose is standard.

- Warning: Some plastics turn yellow or become brittle under radiation. LSR is usually stable here.

Advanced Manufacturing Techniques

Micro-Injection Molding (µIM)

Micro-scale medical molding is used for parts under 1 gram, like microneedle arrays.

- The Challenge: The “Frozen Layer.” Because the part is so small, the plastic freezes instantly when it hits the mold wall.

- The Fix: We use variotherm methods (rapid heating/cooling) to keep the mold hot during filling so the plastic flows, then cool it instantly to eject.

Metal Injection Molding (MIM)

For surgical tools (stainless steel/titanium), CNC machining is slow and expensive. MIM lets us mold metal powder mixed with a binder, then bake the binder out (sintering). It’s great for high-volume, complex shapes.

Design for Manufacturability (DfM)

We run DfM reviews to catch errors on paper before we cut steel.

- Uniform Wall Thickness:If walls vary in thickness, they cool at different rates.

- Result: Warpage and internal stress.

- Draft Angles:You need a 1 to 3-degree taper on vertical walls.

- Reason: Without it, friction during ejection will drag across the surface, ruining the finish or damaging the part.

- Gate Placement:Where does the plastic enter? If we place it wrong, the “weld line” (where flow fronts meet) ends up in a critical stress area, causing the part to snap under load.

Defect Mitigation

- Sink Marks: Usually caused by thick wall sections or low packing pressure. We fix this by increasing pack time until the gate freezes or thinning out ribs (keep them <60% of wall thickness).

- Weld Lines: We can increase melt temp and injection speed to fuse the lines better.

Next Step

If you have a 3D model, send it over. We can run a mold filling simulation to check for air traps and weld lines before you commit to tooling.

FAQ

Q: Do you have ISO 13485 certification?

A: Yes, ISO 13485:2016. This is the foundation of our quality system, covering risk management and full traceability (DHR).

Q: Can you do Low Volume Molding for testing?

A: Yes. We use Medical Prototypes strategies. We can use hybrid manufacturing (3D printing + molding) or rapid aluminum tooling to make a few hundred parts for clinical trials or market testing. This bridges the gap to mass production.

Q: What material is best for a clear medical device?

A: Polycarbonate (PC) is the standard for clarity and toughness. If you need high heat resistance + clarity, we might look at specialized grades or LSR.

Q: How do you handle Medical injection molding China sourcing risks?

A: Risk is managed through validation. By performing IQ/OQ/PQ and maintaining a complete Device History Record (DHR), we provide the same level of assurance and traceability you would expect anywhere else, but often with better cost structures.

Q: Why use LSR instead of TPE in medical molding?

A: In medical molding, LSR is often preferred because it has a permanent thermoset structure. It won’t melt at high heat (up to 180°C) and remains flexible at -60°C. It is also cleaner and more biocompatible than most TPEs.