This project with “Client O” (a North American portable water system innovator) wasn’t about making a pretty consumer gadget. It was about survival. Their water purification units live in the back of overland expedition trucks and marine vessels.

The vibration is constant. The moisture is aggressive.

If this device fails, someone is stuck in the desert with bad water.

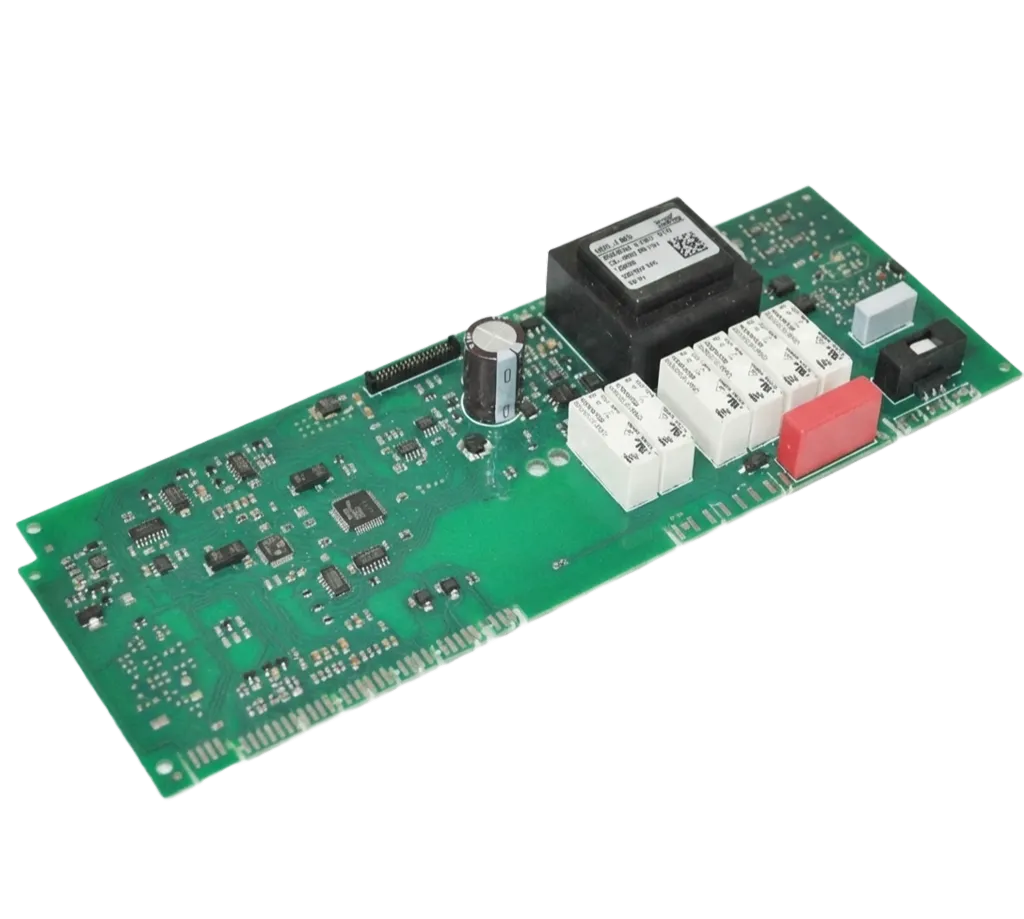

i am writing this engineering log to explain exactly how Shanbo and our brother company, PS Electronics, managed the Electromechanical Assembly Services to keep these units running when the pavement ends. This covers the transition from a standard PCB design to a fully ruggedized Turnkey Box Build Assembly.

The Electronics: Why Standard Protection Failed

Client O came to us with a solid PCB design featuring high-power UV-C LEDs for sterilization. Their initial request was standard conformal coating. It is cheap, fast, and standard for many consumer electronics.

We had to push back.

Here is the reality of providing Electromechanical Assembly Services and Electronic Product ODM for harsh environments: conformal coating creates a film typically 25–250 microns thick. That is roughly the thickness of a sheet of paper or two. It prevents oxidation and stops minor humidity, but it provides zero structural support.

When a 4×4 truck hits washboard roads for six hours, components on the board start to resonate. Without support, the heavy components (like the inductors and the UV-C module) will fatigue the solder joints.

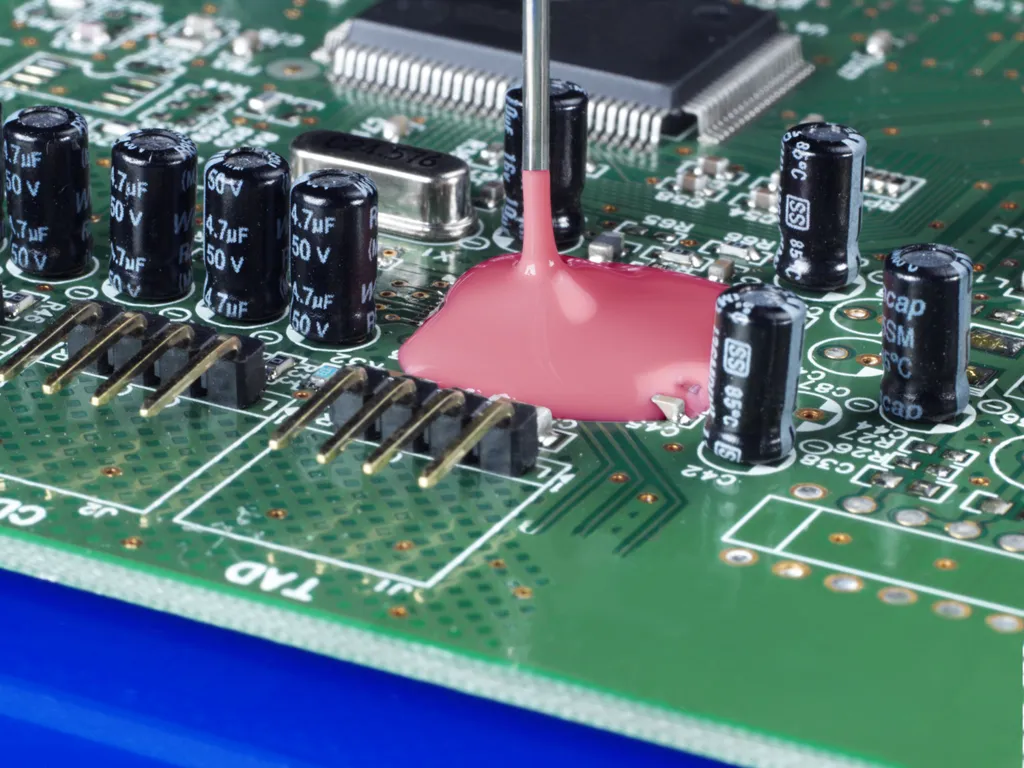

The Fix: We moved to potting (encapsulation).

Potting encases the entire PCBA in a liquid compound that cures into a solid or gel-like mass, usually 1–10 mm thick. This creates a monolithic block. The components can’t move.

The Thermal-Mechanical Conflict (And our Failure Record)

Potting sounds easy—just pour glue on it, right?

No. We nearly killed the first prototype batch.

We initially looked at using a standard Epoxy resin. Epoxies are strong and adhere well to everything.

- The Problem: Epoxy is rigid.

- The Failure Mode: Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) mismatch.

When the device heats up (from the LEDs) and cools down (nighttime in the desert), the board and the potting material expand at different rates. Rigid epoxy is too stiff; it refuses to move. This stress channels directly into the components. In some thermal cycling tests, rigid potting can reduce the life of solder joints by over 90%.

We saw hairline cracks in the solder joints during the thermal shock test (-65°C to 125°C). The epoxy was literally pulling the components off the board.

The Revision:

We switched to a Polyurethane (PU) Compound.

Polyurethanes are softer and have an elastomeric nature. They act like a shock absorber. When the board expands, the PU stretches.

We also had to worry about the “Reversion” issue with old PU formulas (where they turn back into goo in high humidity). We sourced a newer formulation.

- Spec Check: The datasheet claims hydrolytic stability at 100°C and 95% relative humidity.

- Result: It passed the IPC-CC-830 Hydrolytic Stability test.

Solving the Heat Problem

The UV-C LEDs generate significant heat. A standard unfilled epoxy or urethane acts like a blanket.

- Standard thermal conductivity: 0.14–0.2 W/m·K.

- Result: The LEDs would overheat and burn out inside the block.

We used a specialized potting mix filled with Aluminum Oxide.

- New thermal conductivity: > 1.0 W/m·K.

This turns the entire potting block into a heat sink, pulling thermal energy away from the sensitive LEDs.

Custom Plastic Housing: Selecting the Armor

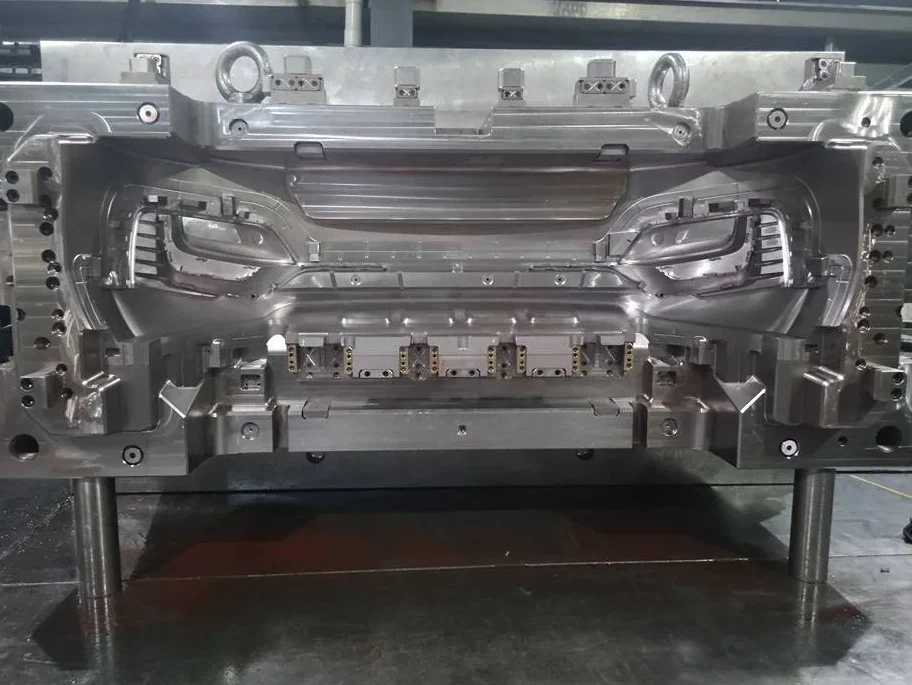

While PS Electronics handled the chemical engineering inside, Shanbo had to build the Custom Plastic Housing. This material selection is a critical step in our Electromechanical Assembly Services, ensuring the shell protects the internals we just ruggedized.

Client O originally considered ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene). It’s the “vanilla” choice for plastic enclosures. It is cheap and rigid.

But ABS has an Achilles’ heel: UV radiation. Sunlight breaks down the polymer chains in standard ABS, making it yellow and brittle. For a device mounted on the deck of a boat, this is unacceptable.

We evaluated the options for OEM Electromechanical Manufacturing:

Calculation Note:

We chose Polycarbonate (PC) primarily for impact strength. If a user drops this unit on a rock, PC yields; ABS cracks. While ASA has better weather resistance than ABS, PC offers the best balance of toughness and optical clarity (useful for the LED indicators).

(Note: We need to monitor the injection gate location on the next mold trial; the knit line looks a bit weak near the screw boss).

Waterproofing: The Math Behind the Seal

This is where many general Electromechanical Assembly Services providers fail. It is not about making it watertight today. It is about making it watertight five years from now.

The enemy is Compression Set (CS).

Elastomers (rubbers) are viscoelastic. If you squeeze them, they push back. But over time, they get lazy. They permanently deform and stop pushing back.

If the sealing force drops below a critical threshold (usually around 1 N/cm), water gets in.

The Gasket Choice

We used EPDM rubber.

- Why? EPDM is the king of outdoor weathering. It ignores Ozone and UV.

- Why not Neoprene? Neoprene is better for oil resistance, but EPDM beats it on pure weathering. Since this unit isn’t sitting in a puddle of diesel, EPDM is the safer bet for longevity.

The FEA Prediction

We didn’t just guess the screw torque. We used Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to model the seal lifespan.

The Draft Calculation:

- Initial Compression: We designed the groove to compress the gasket by 35% (Target is 25-40%).

- CS Factor: We assumed a 50% loss of sealing force over 10 years due to thermal cycling fatigue.

- Fastener Spacing: We adjusted the screw locations to ensure the housing didn’t bow between screws.

The FEA showed that even with the housing expanding in the heat (thermal deformation), the residual pressure on the gasket stays safe.

Important: We strictly avoided the “cumulative” trap of IP ratings.

Client O needed IP67.

- IPX7: Immersion (1 meter). This tests if the seal holds static pressure.

- IPX6: Water Jets (100 L/min at 100 kN/m²). This tests if the seal deforms under dynamic blast.

A housing can pass immersion but leak under a jet spray because the jet pushes the gasket inwards. We tested for both.

The Testing Protocol

You cannot verify a rugged product with a 3D print.

We tried.

Failure Record: We printed a prototype case to test the fit. It leaked immediately.

Reason: FDM prints have microscopic pores between layers. Even SLA prints can warp. For IP ratings above IP55, you basically need the real injection molded part or a high-quality CNC machined prototype.

Our validation checklist (based on IEC 60529):

- Dust Tight (IP6X): Vacuum test.

- Water Jet (IPX6): 12.5mm nozzle, 100 liters/minute. It is like a fire hose.

- Immersion (IPX7): Submerged tank for 30 mins.

- Dielectric Withstand: 1500 VDC for one minute. (Because the potting prevents arcing).

FAQ: Technical & Process Questions

Q1. Why did you chose potting over conformal coating?

Conformal coating is just a thin skin (25–250 microns). It stops corrosion, but it has zero mechanical strength. For a device vibrating in an engine bay or a boat hull, the heavy components on the PCB will eventually crack the solder joints due to fatigue. Potting (1–10mm thick) locks everything in a solid block. It is vital for vibration resistance.

Q2. Can Shanbo handle the electronics sourcing too?

Yes. That is the point of the Electronic Product ODM service. Our brother company, PS Electronics, handles the component sourcing, SMT assembly, and potting. Shanbo handles the mold making, injection molding, and the final Turnkey Box Build Assembly. It prevents the usual “it’s the other factory’s fault” argument when the PCB doesn’t fit the box.

Q3. Is IP67 good enough for pressure washing?

No. Standard pressure washing is closer to IP69K (80°C water at 1450 psi). IPX6 is a strong hose, but not high-pressure steam. If your application involves industrial washdowns (like food processing equipment), you need to specify IP69K, which requires totally different housing materials to resist the heat deformation.

Q4. Why did the first thermal shock test fail?

We used a generic epoxy that was too rigid. When the temperature dropped to -65°C, the epoxy shrank faster than the PCB. The stress was so high it sheared the components off the board. We switched to a modified Polyurethane which is more flexible and absorbs that CTE (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion) mismatch.

Q5. How long will the waterproof seal last?

It depends on the “compression set” of the gasket. All rubber loses its bounce over time. By using FEA (Finite Element Analysis) and high-grade EPDM, we design the seal to maintain enough pressure (>1 N/cm) for the expected service life (usually 5-10 years), even after the rubber degrades slightly.

Ready to build something that lasts?

We don’t just assemble parts; we engineer the reliability. If you need Electromechanical Assembly Services for products that must survive outside the lab, send us the drawings.